Ancient Bradenese

Uh oh, fictional history ahead! This article is based in fictional historical events and is not to be taken seriously. |

Ancient Bradenese Civilization Khisirūthū | |

|---|---|

|

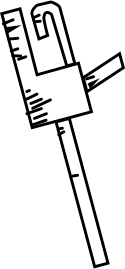

A standard used by the Ancient Bradenese which functioned as a flag. | |

| Capital | various, including Per-Thū, Ha-Per, Ben-Ja, Kawnafthū, Lunēti and Per-Hasirothū-Ahtothū (importance varies by time period) |

| Demonym(s) | Sirūthū |

| Government | Absolute Monarchy |

• Kha iyat | None, office dissolved |

| Establishment | Between 3000 and 2750 B.C.E. |

| Today part of | |

The Ancient Bradenese (Khisirūthū in Ancient Bradenese) were an ancient civilization in what is now the Republic of Bradenland. It began to form around 3000 BC (according to scholarly chronology) and was founded with the territorial unification of its' heartland under Ak-Ha (reigned c. 2850-2790 BC). Centered on the cities of Per-Thū and Ha-Per, the empire exercised influence over a wide area that often included other nations. The history of the Khisirūthū civilization is often divided by scholarly chronology into three 'empires', which were periods of prosperity and political stability, as well as three 'intermezzos', which were periods of strife and political disunity.

The civilization reached the apex of its power under the rulers of the 'New Empire' (i.e. Ahto-Ha-Thu-Lan, Thusiroben, Hasirothu-Ahtothu II) between 1500 and 1100 BC, even ruling much of a nearby country called Metia, after which it began to slowly decline until it fizzled out after 1 AD.

With lots of natural resources, and a need to keep track of them, the administration created a writing system used to encode their language, often called 'medu Khisirūthū' (English: Speech of the Khisirūthū), and began to further exploit the natural resources through massive farming and mining projects, as well as trade with the nearby Metians and the people of the cities of Hakto and Nido further south, and lead extensive military campaigns. In charge of managing these activities were scribes, priests, and governors under the leadership of the 'Kha iyat' (English: Great King) who guaranteed the unification, protection, and wellbeing of the people.

History

Pre-unification

As soon as 4000 BCE and possibly as early as 4500 BCE, tribes developed into a "proto-culture" of sorts, showing knowledge in farming and keeping livestock. Starting around 3000 BCE, there were several independent polities in the region. In the time frame of 1000 years, the culture had grown from simple farming into a stable and powerful civilization where the leaders had firm control. Some centers of this culture include Per-Thū and Ha-Per. The material culture included several fine works, including pottery, gemstones, and jewelry. Towards the very end of the period, the city of Per-Thū grew to such dominance that it began to control the other polities in the region.

The Early Dynastic Period, c. 2850 - c. 2450 BC

The historian Man-Thū-Tan of Ha-Per categorized the long history of rulers from the unification to his own time (around 180 BC) into a series of dynasties. He began this history by including Neb, the so-called "Ancient of This (Per-Thū)," often credited with the unification into one state.

Ak-Ha is known to Bradenese historians to have been the same as Neb, and the unifier of the several polities of Ancient Bradenland into one state. During the First Dynasty, as given by Man-Thū-Tan, the earliest of the dynastic rulers moved the administrative capital to Ha-Per, where they could control the agriculture of both halves of his kingdom, as well as important trade routes leading to Hakto. The power of the kings of the First Dynasty was exemplified by the facts that they built larger tombs than their pre-unification predecessors, with more lavish funerary objects within. The important institution of kingship was important to hold control over the civilization's land, labor, and resources.

The Old Empire, c. 2450 - c. 2200 BC

The developments of the Early Dynastic Khisirūthū led to the Old Empire, the first of three golden ages. Major technological, artistic, and architectural advancements were made during this period, which was fueled by an increase in agricultural production, made possible by a strong administration. Some of the most important works of the Ancient Bradenese civilization, like the Tomb of Akben, were constructed during the Third Dynasty of the Old Empire. The advisor was in charge of appointing officials on behalf of the King. These officials collected taxes, initiated agriculture projects, and established a system of justice.

The central government also grew more powerful as a class of skilled workers became allowed to participate in government jobs. These officials were granted wealth by the King as payment for their work. Eventually these officials began to overshadow their king in power as the economy began to decline. Regional governors became increasingly more powerful and began to challenge the authority of the power of the king. This, along with unfavorable climate conditions, led to the rapid decline and the beginning of the First Intermezzo of strife which lasted for about 150 years.

The First Intermezzo, c. 2200 - c. 2050 BC

After the central government collapsed at the end of the Old Empire, the administration was no longer able to support the state economy. The provincial governors could not rely on the power of the king to support them, and there was a national food shortage. This led to famines and small wars. The provincial governments, no longer needing to pay tribute to the king in Ha-Per, established their own independent states. These local rulers began clashing with each other for control. Around 2150 BC, a line of rulers from the city of Lunēti declared themselves kings, while their rival, the Provincial Governor Nebmit in Per-Thū, took control of many of the nearby provinces and declared himself the king. A descendant of Nebmit, Thu-Nēbse defeated the kings of Lunēti and reunified the nation.

The Middle Empire, c. 2050 - c. 1675 BC

Starting with kha iyat Thu-Nēbse, the kings of the Middle Empire restored the country's stability and prosperity, sparking a renaissance of art, architecture, and literature. Thu-Nēbse and the following kings from the Ninth Dynasty ruled from Per-Thū, but Nebmit-Ka-Thūse, upon assuming the kingship and starting the Tenth Dynasty, moved the capital to the city of Kawnafthu. On top of that, the military conquest of Metian territory had even more natural resources.

With the country having been secured politically and militarily and with plenty of resources to use, national population, religion and arts thrived. Sculpture and relief from this period is very detailed and shows much sophistication in its handiwork.

However, towards the end of the Tenth Dynasty and beginning of the Eleventh (c. 1800 BC), a people group called the Lakhat entered the lands of the Khisirūthu as part of an operation to recruit workers to build large projects. King Mero-Nebmit, one of the last kings of the Tenth Dynasty commissioned these projects, which began to weaken the economy. This, along with food shortages, began a decline that would culminate in the Second Intermezzo. Meanwhile, during the Eleventh Dynasty, the Lakhatian settlers gained more power and influence, eventually coming in control of the country around 1675 BC.

The Second Intermezzo, c. 1675 - c. 1550 BC

As the power of the kings of the Middle Empire weakened around 1780 BC, the Lakhatian working force eventually gained more and more power. They became known as the 'Khamesti' (English: Foreigners) and they made their capital in the city of Lunēti, which was close enough to the capital Kawnafthu to make the central government relocate to Per-Thū. To make matters worse, productive territories of Metia under the suzerainty of the Khisirūthu, were invaded and taken by Fasu, king of Metia, which for the time being, replaced the Khisirūthū as the most powerful nation in the region.

In 1675 BC, a battle between the Khamesti and the Khisirūthū would lead to the destruction of the ruling dynasty, the establishment of a Khamesti Twelfth Dynasty and the placement of a puppet Thirteenth Dynasty in power. This polity was in immediate danger of invasion by the Metians and the Khamesti. After sixty years of vassalage, the new Fourteenth Dynasty challenged the Khamesti. Major offensives by kings like Tiū I and II defeated the Metians, but could not push back the Khamesti. That was up to Ahto-Ha-Thū-Lan, who drove the Khamesti out in 1555 BC and founded the New Empire, establishing a new dynasty that was one of the most powerful in the history of the Khisirūthū.

The New Empire, c. 1550 - c. 1075 BC

Restoration of the Empire

The Kha iyats of the Fifteenth Dynasty of the New Empire established a period of unbridled prosperity without precedent in their history. They did this by securing the border territories, especially those right next to the Empire of the Haktotians (Khi iyat Haktō in ancient Bradenese). King Thū-Sirō-Ben was the first to need to deal with the Haktotians, as they waged regular campaigns in Khisirūthū territory. The military leaders believed that the best defense is a good offense, so they petitioned the Kha iyat to conscript one out of every twenty able-bodied men to fight in the Haktotian war. The consequences of this were successful, though it was only the first of a long series of wars with the Haktotians. Conquests made by Kha iyat Thusiroben and his successors expanded the Khisirūthū state to the largest it had ever been.

Empire building, 1475-1325 BC

Following Thusiroben came Queen Nēb-nafthū Thū-sirō-ben. Nebnafthu sought to expand her influence by trade and culture reforms. She restored temples previously destroyed by the Khamesti and the Metians, and sent trading expeditions all the way to Muthu, another far away kingdom. Following Nebnafthu-Thusiroben reigned Nebsirothu I, whose conquests were far reaching, exploiting various commodities.

Following Nebsirothu I came two kings of the same name. Kha iyat Nebsirothu II secured the southern border even further after engaging in a momentous battle with the Haktotians in 1432 BC. Believing that Khisirūthū-Haktotian peace was obtainable, Nebsirothu III, his son, made a treaty with the King of Hakto to never invade each other again. After this, the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty focused on theology. King Merut-siro-thū I succeeded Nebsirothu III around 1380 BC. He was the greatest contributor to the Great Temple of Ha in Ha-Per. Merutsirothu I made important reforms to the temples across his country.

The reigns of Hasirothu-Ahtothu II and his successors

A century afterwards, the Sixteenth, or Hasironid Dynasty, took power. Its most famous king, Hasirothu-Ahtothu II (d. 1234 BC) restored the country to its former glory after 50 years of dilapidation. He was known as a powerful and wealthy king, retaking territories lost by his predecessors. Following the reigns of Meronben and Siroben, Hasirothu-Ahtothu III (d. 1155 BC) came to power. The last great king of the New Empire, his reign saw the weakening of neighboring countries. Some, like Muthu, were even destroyed. The Khisiruthu state held up for slightly longer, however it collapsed too, ushering in the Third Intermezzo.

The Third Intermezzo, c. 1075 - c. 650 BC

Following the collapse of most of the ancient nations perhaps induced by the Bronze Age Collapse, the empire fell into a third stage of dilapidation called the Third Intermezzo.